Mark Twain the Greatest American Novelist…And One of the Greatest American Travel Writers!

For all the recognition that Mark Twain receives as America’s first, and some would say greatest American novelist, a theme that flows through all of Twain’s work is travel and movement and all that travel led to Mark Twain writing some of America’s greatest travel books, including:

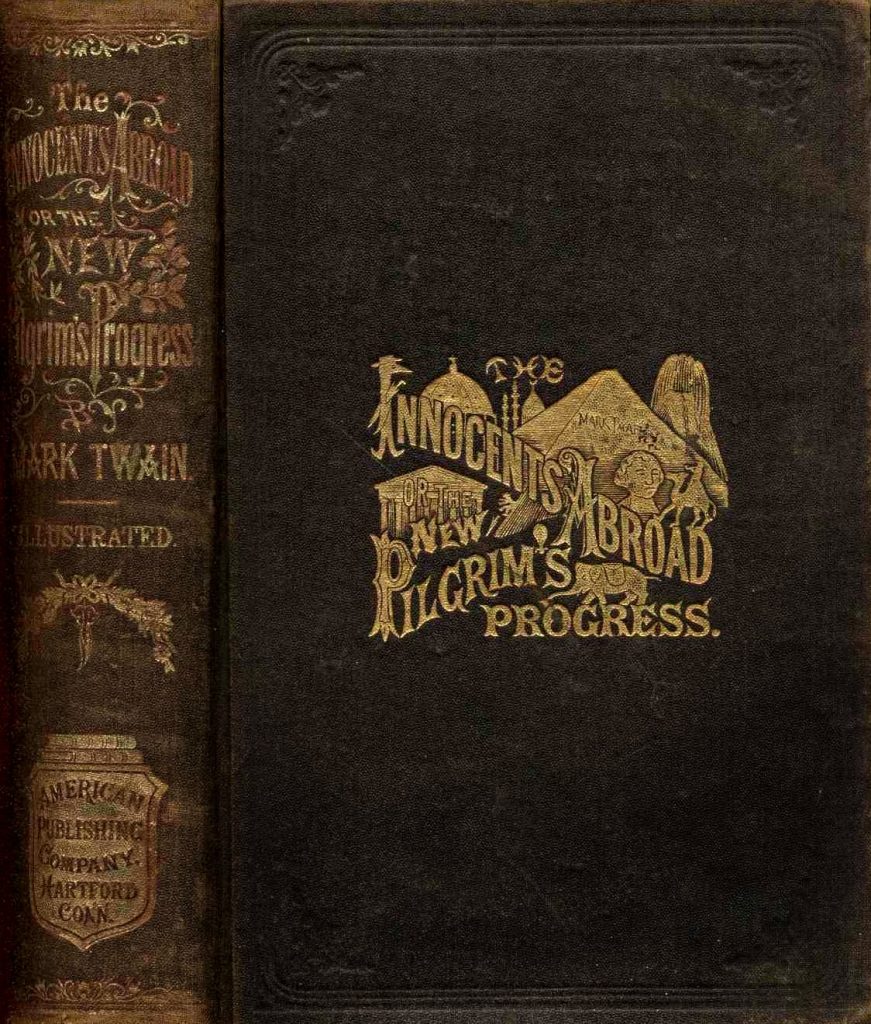

The Innocents Abroad, 1869, Mark Twain in Europe on a Boat

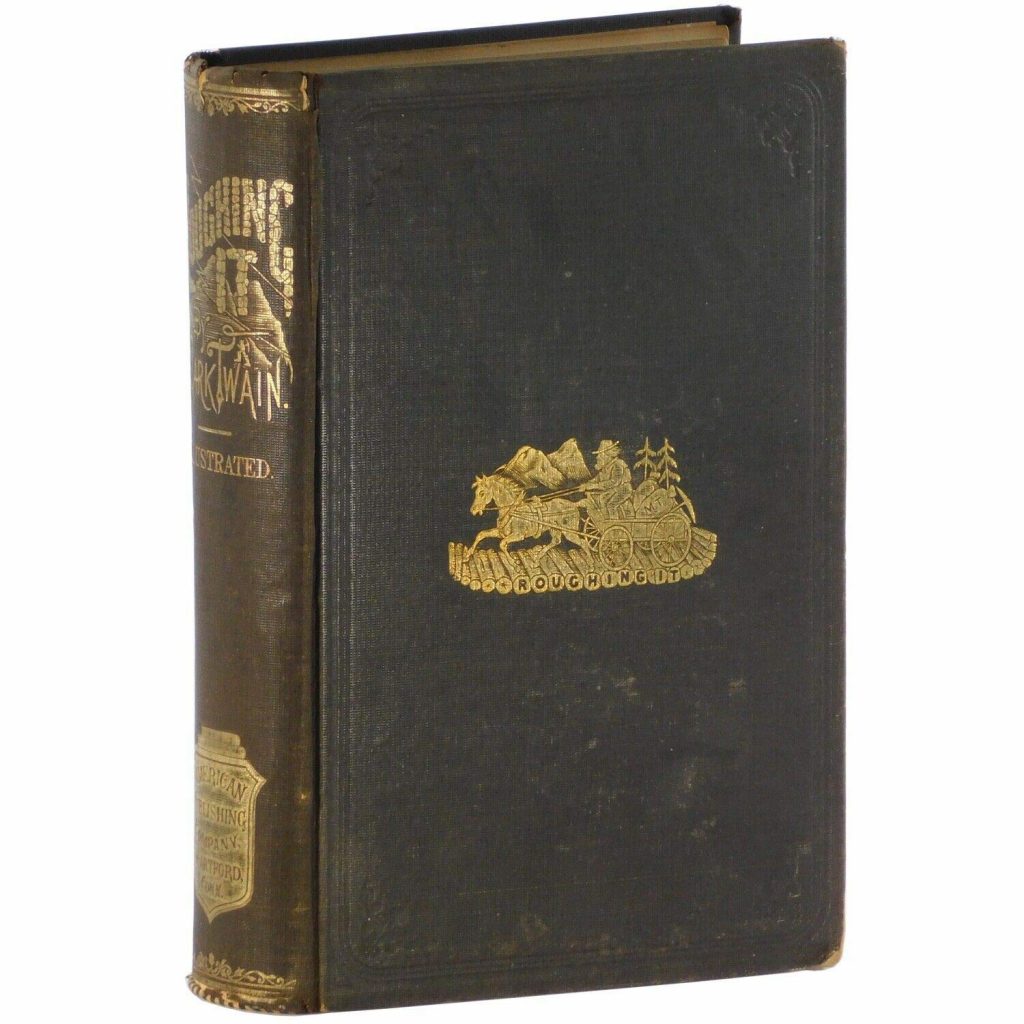

Roughing It, 1872, Mark Twain in the American West

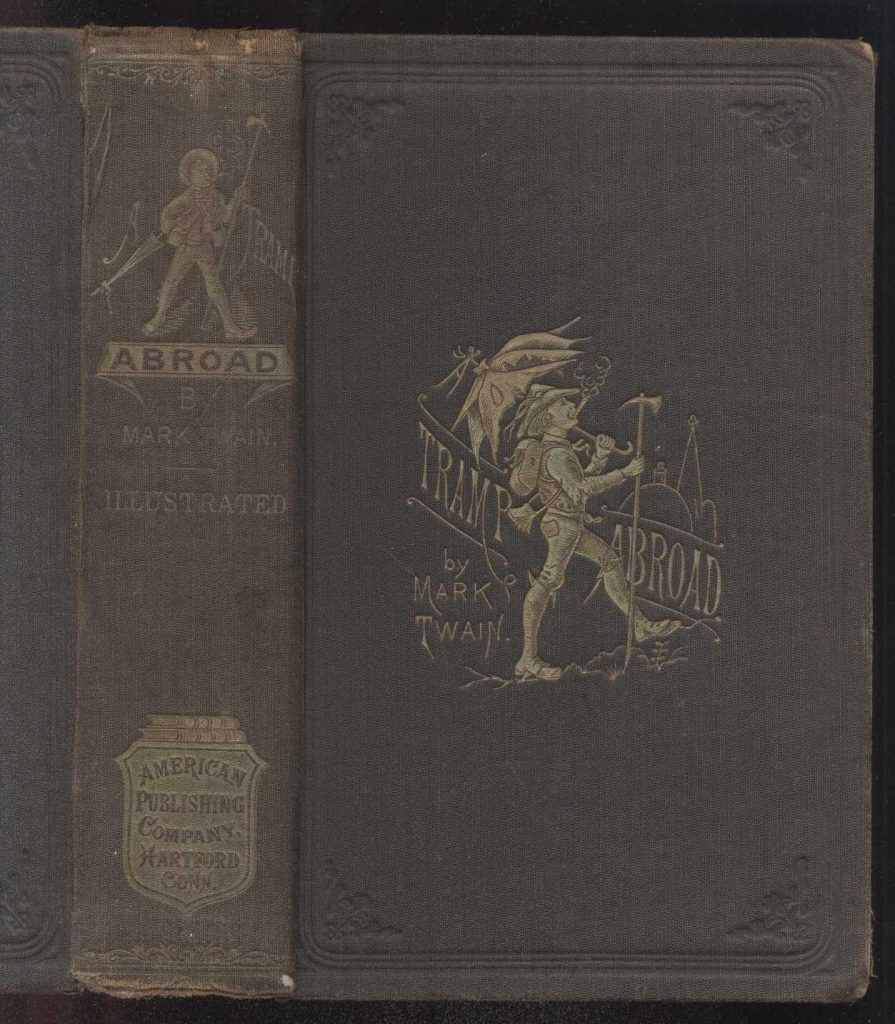

A Tramp Abroad, 1880, Mark Twain in Europe on Foot

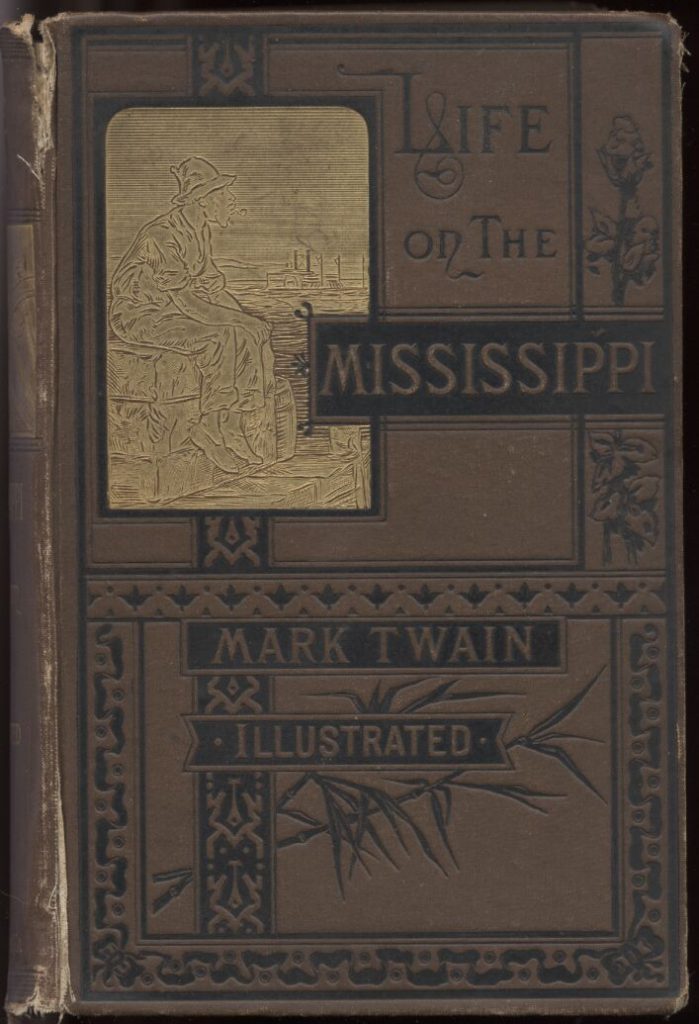

Life on the Mississippi, 1883, Mark Twain on a Boat on the Mississippi River

Following the Equator, 1897, Mark Twain circling the world on a Boat

In A Tramp Abroad (1880), especially the Blackstone Publishing Audio Version, one gets a sense of Mark Twain at a time when he was struggling to see what direction his writing career was headed between his two most famous novels, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876) and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884), something Ben Crair touches on in a piece on Mark Twain’s walking Europe that led to A Tramp Abroad for the New York Times in 2016:

Mark Twain Found Inspiration in Germany (Though Not German), Ben Crair, New York Times

“When Twain arrived in Germany, his writer’s block had hamstrung not only “Huckleberry Finn” but also several other books, including “Life on the Mississippi” and “The Prince and the Pauper.” And he had humiliated himself in December 1877 with an irreverent speech in Boston before some of America’s greatest literary figures: Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and Oliver Wendell Holmes. “I feel that my misfortune has injured me all over the country,” he wrote to a friend. He told his mother that he needed to “fly to some little corner of Europe.”

I arrived in Heidelberg in June with some sense of Twain’s restlessness. When I told a friend that I was having trouble concentrating, he said I should stay present: open my senses to whatever was happening at the moment, and exist in the world instead of in my head. As I reread “A Tramp Abroad,” knowing that Twain had arrived in Germany under a cloud of shame and failure, it seemed to me that he had faced a similar challenge. His goal was not so much to penetrate Heidelberg and the Neckar Valley but to soak his senses in those places, to dissolve his insecurity in the scenery and to rediscover his pride and purpose.

This comes through clearest in Twain’s Neckar narrative, so I followed him upriver. From Heidelberg, I took a boat to Neckarsteinach, an old town with a quartet of castle ruins. The river winds between hills like a lazy cursive signature. Time has worked slowly on its banks: The terrain is still mainly field and forest; the mountains robed in thick green foliage. Every few miles our boat passed a village with bored-looking teenagers and rows of simple white homes. After sundown, the buildings glowed like votive candles in the dark.

The inns where Twain stayed along the Neckar have closed, but some of his favorite castle ruins are now connected with hotels. Burg Hornberg is a mountaintop fortress surrounded by terraced vineyards, with a tower so high that surely, at some point, someone must have locked a princess in it. The hotel’s impressive view of the Neckar is marred only slightly by an industrial plant.

Farther downstream, you can stay at the Schlosshotel Hirschhorn, whose ruins were one of Twain’s favorite Neckar sights. “The clustered brown towers perched on the green hilltop, and the old battlemented stone wall, stretching up and over the grassy ridge and disappearing in the leafy sea beyond, make a picture whose grace and beauty entirely satisfy the eye,” he wrote in “A Tramp Abroad.””

Maybe indeed it was Mark Twain’s trip to Europe in 1879 and subsequent book A Tramp Abroad that led to Twain diving back into The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, but let us linger for a moment on a hilarious chapter from A Tramp Abroad, A Trip To Rigi, that has Twain and his traveling companion “Harris” in the Lucerne/Weggis, Switzerland area (a place that Twain and his family came to love) climbing the Rigi-Kulm Alpine mass >

A Trip To Rigi, A Tramp Abroad, (Marc Twain 1879)

“The Rigi-Kulm is an imposing Alpine mass, six thousand feet high, which stands by itself, and commands a mighty prospect of blue lakes, green valleys, and snowy mountains–a compact and magnificent picture three hundred miles in circumference. The ascent is made by rail, or horseback, or on foot, as one may prefer. I and my agent panoplied ourselves in walking-costume, one bright morning, and started down the lake on the steamboat; we got ashore at the village of Waeggis;

three-quarters of an hour distant from Lucerne. This village is at the foot of the mountain.

We were soon tramping leisurely up the leafy mule-path, and then the talk began to flow, as usual. It was twelve o’clock noon, and a breezy, cloudless day; the ascent was gradual, and the glimpses, from under the curtaining boughs, of blue water, and tiny sailboats, and beetling cliffs, were as charming as glimpses of dreamland. All the circumstances were perfect–and the anticipations, too, for we should soon be enjoying, for the first time, that wonderful spectacle, an Alpine sunrise–the object of our journey. There was (apparently) no real need for hurry, for the guide-book made the walking-distance from Waeggis to the summit only three hours and a quarter. I say “apparently,” because the guide-book had already fooled us once–about the distance from Allerheiligen to Oppenau–and for aught I knew it might be getting ready to fool us again. We were only certain as to the altitudes–we calculated to find out for ourselves how many hours it is from the bottom to the top. The summit is six thousand feet above the sea, but only forty-five hundred feet above the lake. When we had walked half an hour, we were fairly into the swing and humor of the undertaking, so we cleared for action; that is to say, we got a boy whom we met to carry our alpenstocks and satchels and overcoats and things for us; that left

us free for business. I suppose we must have stopped oftener to stretch out on the grass in the shade and take a bit of a smoke than this boy was used to, for presently he asked if it had been our idea to hire him by the job, or by the year? We told him he could move along if he was in a hurry. He said he wasn’t in such a very particular hurry, but he wanted to get to the top while he was young. We told him to clear out, then, and leave the things at the uppermost hotel and say we should be

along presently. He said he would secure us a hotel if he could, but if they were all full he would ask them to build another one and hurry up and get the paint and plaster dry against we arrived. Still gently chaffing us, he pushed ahead, up the trail, and soon disappeared. By six o’clock we were pretty high up in the air, and the view of lake and mountains had greatly grown in breadth and interest. We halted awhile at a little public house, where we had bread and cheese and a quart or

two of fresh milk, out on the porch, with the big panorama all before us–and then moved on again.

Ten minutes afterward we met a hot, red-faced man plunging down the mountain, making mighty strides, swinging his alpenstock ahead of him, and taking a grip on the ground with its iron point to support these big strides. He stopped, fanned himself with his hat, swabbed the perspiration from his face and neck with a red handkerchief, panted a moment or two, and asked how far to Waeggis. I said three hours. He looked surprised, and said: “Why, it seems as if I could toss a biscuit into the lake from here, it’s so close by. Is that an inn, there?”

I said it was.

“Well,” said he, “I can’t stand another three hours, I’ve had enough today; I’ll take a bed there.”

I asked:

“Are we nearly to the top?”

“Nearly to the TOP? Why, bless your soul, you haven’t really started, yet.”

I said we would put up at the inn, too. So we turned back and ordered a hot supper, and had quite a jolly evening of it with this Englishman.”

The rest of the A Trip To Rigi chapter is just as entertaining and it’s not hard to imagine climbing Rigi-Kulm with Twain and Harris and laughing all the way up and all the way down, which was on a steep train back down that is well worth your time later in the same chapter!

A Trip To Rigi, A Tramp Abroad, (Marc Twain 1879)

A couple more New York Times recent pieces on Mark Twain’s travels are….

Twain’s Nicaragua,144 Years Later, Freda Moon, New York Times, September 16, 2010

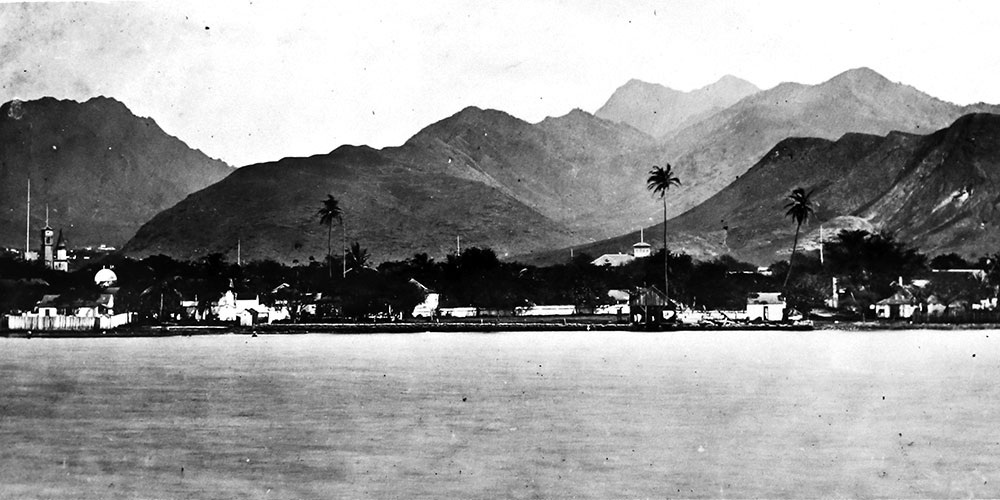

Mark Twain’s Hawaii, Lawrence Downes, New York Times, May 14, 2006

….and the below excerpt from Downes piece of Twain in Hawaii, which was included in his book Roughing It, is an observation that one often hears when they read Twain’s travelogues on how well Twain’s writing holds up even 100+ years later >

“Hawaii has seen its share of famous storytellers. Robert Louis Stevenson, Jack London and Herman Melville passed through on their way to other frontiers. But what little they wrote about Hawaii was fictionalized, heavily metaphorical and is now mostly forgotten. James Michener, on the other hand, wrote way too much: His 1959 novel “Hawaii” covers nearly the whole thing, from the volcanoes to the missionaries, a span of 40 million years, or maybe pages, it’s hard to tell. (“And then one day,” one typically fizzy passage goes, “at the northwest end of the subocean rupture, an eruption of liquid rock occurred that was different from any others.”)

That book is a brick, and so is the movie, even if it does have Julie Andrews, that pearly shell, playing a missionary’s wife. Neither is what you want if you’re looking for something to enrich your visit.

What you want is Mark Twain.

Twain spent four months in the islands in 1866, when he was 31 and working on becoming famous. His 25 letters from the Sandwich Islands, written on assignment for The Sacramento Union, are still fresh and rudely funny after almost a century and a half — a foretaste of genius and the best travel writing about Hawaii, my home state, I have ever read.”

“Mark Twain stood on the deck of the Warrimo as O‘ahu came into view.

“On the seventh day out we saw a dim vast bulk standing up out of the wastes of the Pacific and knew that that spectral promontory was Diamond Head, a piece of this world which I had not seen before for twenty-nine years,” Twain wrote. “So we were nearing Honolulu, the capital city of the Sandwich Islands—those islands which to me were Paradise; a Paradise which I had been longing all those years to see again. Not any other thing in the world could have stirred me as the sight of that great rock did.”

The year was 1895. Twain was 69. We can imagine the great author and lecturer on deck—mop of white hair blowing in the trade winds, shaggy mustache drooping over his mouth, taking a couple puffs on one of the cigars that seemed to always be clamped between his teeth. It was sunset.

“The vast plain of the sea was marked off in bands of sharply-contrasted colors: great stretches of dark blue, others of purple, others of polished bronze; the billowy mountains showed all sorts of dainty browns and greens, blues and purples and blacks, and the rounded velvety backs of certain of them made one want to stroke them, as one would the sleek back of a cat.””

Mark Twain is yes indeed one of America’s greatest novelists, but his travel writing is a must as well for those that like Twain are energized by traveling, movement, and adventure which is at the heart of what The Mark Twain Trail is all about!

The Mark Twain Trail

3827 South Carson Street

Unit 505-25 #1022

Carson City, Nevada 89701

info@marktwaintrail.com

775 372 – 7200