Mark Twain Understood What Motivated Mobs – Twain On the Evil of Lynching in America at Beginning of 20th Century

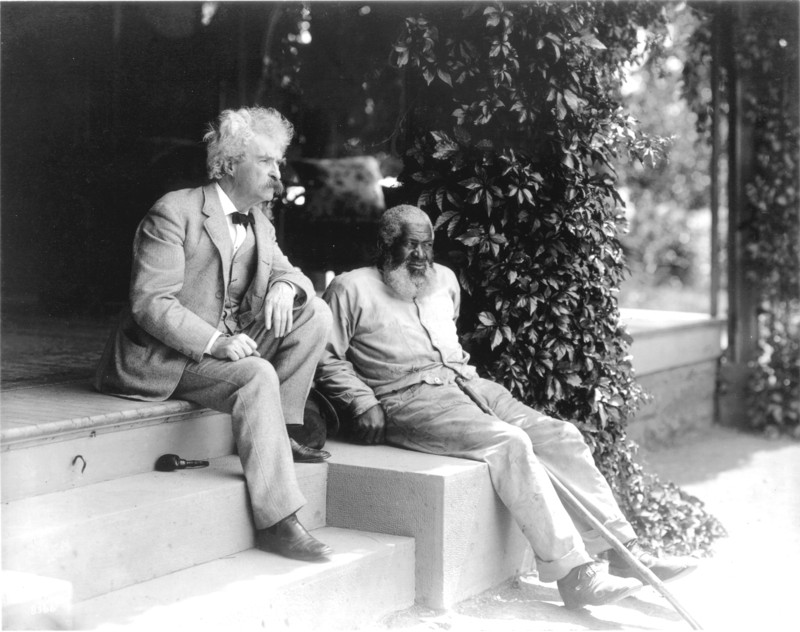

If there is one thing not well understood about Mark Twain it is the massive transformation he went through from a Southern Boy who grew up on the Mississippi River in Missouri with opinions on race and society shaped by his family and those around to him, to one of the most well-traveled human beings on Earth with enlightened views on everything that he struggled on whether to make known to the general public or not. Twain left behind not only his Autobiography not to be published until 100 years after his death in April 1910, but also dozens of essays like The United States of Lyncherdom which laments the rise of lynching of African-Americans in America and in particular a lynching in his home state of Missouri.

Niolaus Mills, a professor of literature at Sarah Lawrence, recently wrote about Twain’s The United States of Lyncherdom essay in relation to the January 6, 2021 attack on the US Capitol Building, and how Twain understood what motivates a group like the one that conducted the attack on the US Capitol:

Mark Twain Understood What Motivated Mobs, Nicolaus Mills, The Dispatch

“When it comes to putting the January 6 siege of the Capitol in perspective for the upcoming Senate trial of Donald Trump, the 80-page brief filed by the House impeachment managers is thorough, as are two are two shorter, academic essays–Yale historian Timothy Snyder’s “The American Abyss,” and foreign-policy expert Mark Danner’s “Be Ready to Fight.”

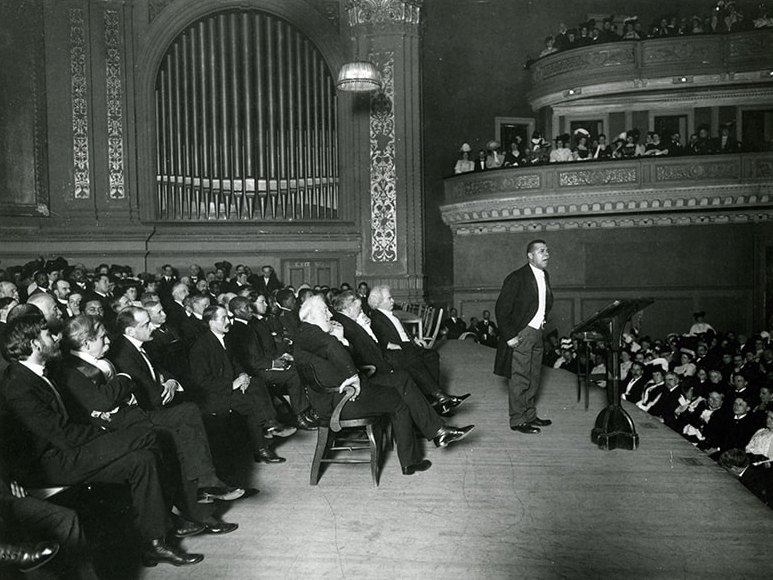

There is, however, another writer who should be read as the Senate trial begins: Mark Twain. Twain never imagined the Capitol being trashed by an angry mob, but in his 1901 essay, “The United States of Lyncherdom,” he foresaw how a mob, like the ones he knew as a Southerner, could terrorize a major, northern city. For Twain, the mob was a staple of American life, not an anomaly, and in “The United States of Lyncherdom” he treated the mob as a political force to be reckoned with.

“I may live to see a negro burned in Union Square , New York, with fifty thousand people present, and not a sheriff visible, not a governor, not a constable, not a clergyman, not a law-and-order representative of any sort,” Twain wrote.

Twain was responding to the rise of lynching, the increased influence of the Ku Klux Klan, and the Supreme Court’s landmark 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision that made “separate but equal” the law of the land. But Twain’s essay, written, as he tells readers, in the wake of an incident in Missouri in which a mob lynched three black men and burned the houses of five black families after a white woman was found murdered, goes far beyond the Jim Crow era in which he lived.”

The underlying essay that Twain wrote that Mills refers to is worth every American’s time in 2021 so they can better understand the disastrous impact that Jim Crow laws were having on America in the late 19th and early 20th centuries that people in the public eye like Twain had trouble writing about, because it would no doubt incense a large group of people that Twain hoped would keep reading his books long after his death and thus provide money for his family and estate decades into the future:

The United States of Lyncherdom, Mark Twain, 1901

“[MT wrote this essay in the summer of 1901, in reaction to a newspaper account of the Missouri lynching he mentions at the start. He even thought of using it as the introduction to a subscription book history of lynching in America. He decided, however, not to publish it at all, and told his publisher that if he went ahead with the book on lynching “I shouldn’t have even half a friend left down there [in the South], after it issued from the press.” The essay was published 13 years after his death, by Albert Bigelow Paine, in Europe and Elsewhere.]

I

And so Missouri has fallen, that great state! Certain of her children have joined the lynchers, and the smirch is upon the rest of us. That handful of her children have given us a character and labeled us with a name, and to the dwellers in the four quarters of the earth we are “lynchers,” now, and ever shall be. For the world will not stop and think–it never does, it is not its way; its way is to generalize from a single sample. It will not say, “Those Missourians have been busy eighty years in building an honorable good name for themselves; these hundred lynchers down in the corner of the state are not real Missourians, they are renegades.” No, that truth will not enter its mind; it will generalize from the one or two misleading samples and say, “The Missourians are lynchers.” It has no reflection, no logic, no sense of proportion. With it, figures go for nothing; to it, figures reveal nothing, it cannot reason upon them rationally; it would say, for instance, that China is being swiftly and surely Christianized, since nine Chinese Christians are being made every day; and it would fail, with him, to notice that the fact that 33,000 pagans are born there every day, damages the argument. It would say, “There are a hundred lynchers there, therefore the Missourians are lynchers”; the considerable fact that there are two and a half million Missourians who are not lynchers would not affect their verdict.

II

Oh, Missouri!

The tragedy occurred near Pierce City, down in the southwestern corner of the state. On a Sunday afternoon a young white woman who had started alone from church was found murdered. For there are churches there; in my time religion was more general, more pervasive, in the South than it was in the North, and more virile and earnest, too, I think; I have some reason to believe that this is still the case. The young woman was found murdered. Although it was a region of churches and schools the people rose, lynched three negroes–two of them very aged ones–burned out five negro households, and drove thirty negro families into the woods.

I do not dwell upon the provocation which moved the people to these crimes, for that has nothing to do with the matter; the only question is, does the assassin take the law into his own hands? It is very simple, and very just. If the assassin be proved to have usurped the law’s prerogative in righting his wrongs, that ends the matter; a thousand provocations are no defense. The Pierce City people had bitter provocation–indeed, as revealed by certain of the particulars, the bitterest of all provocations–but no matter, they took the law into their own hands, when by the terms of their statutes their victim would certainly hang if the law had been allowed to take its course, for there are but few negroes in that region and they are without authority and without influence in over-awing juries.

Why has lynching, with various barbaric accompaniments, become a favorite regulator in cases of “the usual crime” in several parts of the country? Is it because men think a lurid and terrible punishment a more forcible object lesson and a more effective deterrent than a sober and colorless hanging done privately in a jail would be? Surely sane men do not think that. Even the average child should know better. It should know that any strange and much-talked-of event is always followed by imitations, the world being so well supplied with excitable people who only need a little stirring up to make them lose what is left of their heads and do things which they would not have thought of ordinarily. It should know that if a man jump off Brooklyn Bridge another will imitate him; that if a person venture down Niagara Whirlpool in a barrel another will imitate him; that if a Jack the Ripper make notoriety by slaughtering women in dark alleys he will be imitated; that if a man attempt a king’s life and the newspapers carry the noise of it around the globe, regicides will crop up all around. The child should know that one much-talked-of outrage and murder committed by a negro will upset the disturbed intellects of several other negroes and produce a series of the very tragedies the community would so strenuously wish to prevent; that each of these crimes will produce another series, and year by year steadily increase the tale of these disasters instead of diminishing it; that, in a word, the lynchers are themselves the worst enemies of their women. The child should also know that by a law of our make, communities, as well as individuals, are imitators; and that a much-talked-of lynching will infallibly produce other lynchings here and there and yonder, and that in time these will breed a mania, a fashion; a fashion which will spread wide and wider, year by year, covering state after state, as with an advancing disease. Lynching has reached Colorado, it has reached California, it has reached Indiana–and now Missouri! I may live to see a negro burned in Union Square, New York, with fifty thousand people present, and not a sheriff visible, not a governor, not a constable, not a colonel, not a clergyman, not a law-and-order representative of any sort.

Increase in Lynching.–In 1900 there were eight more cases than in 1899, and probably this year there will be more than there were last year. The year is little more than half gone, and yet there are eighty-eight cases as compared with one hundred and fifteen for all of last year. The four Southern states, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana and Mississippi are the worst offenders. Last year there were eight cases in Alabama, sixteen in Georgia, twenty in Louisiana, and twenty in Mississippi–over one-half the total. This year to date there have been nine in Alabama, twelve in Georgia, eleven in Louisiana, and thirteen in Mississippi–again more than one-half the total number in the whole United States.–Chicago Tribune.”

To those of us living now in the early 21st Century it’s almost impossible to imagine the racism and evil that existed in America 100+ years ago and continued for decades after well into the 20th century before the US Government began to address the issues of inequality and race on a national level. Mark Twain certainly addressed the issues around racism in his 1884 novel The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, but the structure of American society and the way most Americans viewed African-Americans limited how much Twain could say or write publicly because the “Cancel Culture” of today also existed 100+ years ago and if you went against popular opinion it would most certainly impact your ability sell books to the general public. Mark Twain pushed the envelope almost as much as any American on issues of race and the unequal treatment of African-Americans during his life on Earth, especially in the last three decades of his life, but Twain could only push so far and if Twain was alive today he not only would be heartened to see how far things have come, but also be fascinated to see that he could freely speak out about how far America still has to go.